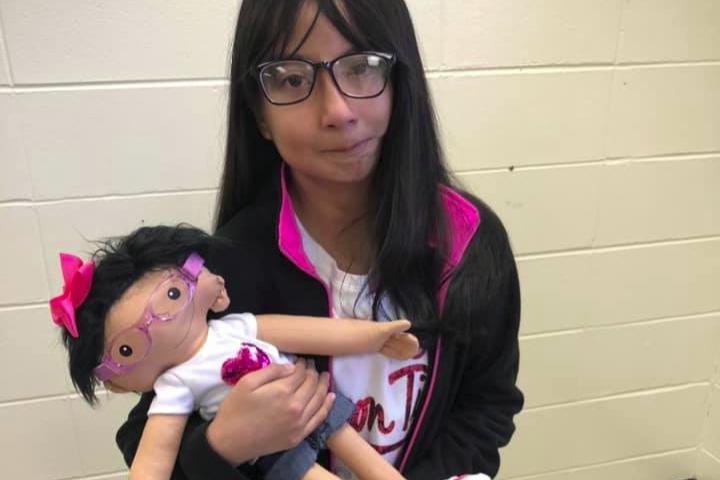

Woman makes "Dolls Like Me" for kids with disabilities

By Mark PygasSept. 30 2024, Updated 8:19 p.m. ET

Today, children's toys and dolls reflect the diversity and inclusivity of modern society. The era of Barbie being just a tall, blonde shopper is over; now, Barbie represents empowered figures like boxing champion Nicola Adams and advocates for social justice, inspired by the groundbreaking themes of the recent blockbuster movie.

But one area where most toys still lag behind is in representing people with disabilities. Amy Jandrisevits, a former social worker in a pediatric oncology unit in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, knows how much dolls mean to kids battling illness.

"In my time working with the kids," she writes. "I used dolls in play therapy to help the children express themselves. Dolls are therapeutic in so many ways — ways that I'm not sure we fully understand. It is a human likeness and by extension, a representation of the child who loves it."

She quickly realized the dolls didn't look much like her patients: "One day I realized that the dolls’ thick hair and perfect health were doing the kids I was working with a disservice as they were often faced with a wide variety of physical challenges."

"Many kids have never have had the opportunity to see their sweet faces reflected in a doll. It's hard to tell a child that they are beautiful but follow it with — but you'll never see yourself in anything that looks like you."

About eight years ago, Amy started making non-traditional Raggedy Ann dolls for the kids in her pediatric unit. "My favorite was a Raggedy Ann for a little girl who was transitioning — green cropped hair and a Ninja Turtle outfit," she writes.

A friend of a friend saw the doll and shared a photo. And that's when Amy got her first request. "A woman whose daughter had just had a leg amputated reached out and asked if I could make a doll for her." Since then, Amy has made over 300 dolls and has a long waiting list.

Parents who can afford the dolls pay around $100 for the creations, which allows Amy to cover the costs for those who can't. "Whatever it costs, whatever I have to do, I’m going to get a doll in the hands of these children," she writes. "This isn’t just a business. It’s the right thing to do."

"Doll-making has allowed me to combine my love of dolls with my passion for social work. I have always been disappointed in the lack of diversity in dolls. So, as my mom taught me, if you don't like it, do something about it!"

“It is so important to show those kids images of themselves," Amy told Today. "Dolls have a power we don’t completely understand."

“It is a really hard sell to tell a kid, ‘You are perfect the way you are,’ and to build self-esteem that way but never offer them anything that looks like them,” she added. "We are going to change the story."

Each doll takes at least seven hours to complete, with Amy closely studying photos of children sent in by parents to make the dolls a perfect match.

“These dolls are loaded with so many emotions,” Amy said. “It is quite amazing to be allowed into people’s lives.”

Amy is currently running a GoFundMe to get dolls to kids whose parents can't afford them, so if you want to see more happy faces like the ones below, you can check it out here. She has already raised over $200,000.

Dolls have even made it as far as Venezuela.

Amy recently made a doll for Sophia Weaver, a 10-year-old with Rett syndrome, Type 1 diabetes, and severe facial deformities, who unfortunately had to enter hospice care. Amy included a colostomy bag and a feeding tube on Sophia's doll.

“When Sophia is no longer here I will be able to hold something that looks like her,” Sophia's mother told Today. “It means the world to me.”

Amy says that her ultimate goal is to have no parents have to pay for something their kids find so comforting during hard times. "If we’re going to look at mental health as a necessary part of medical care, this is key. If you want validation and play therapy, you need these dolls."

This article was originally published on December 10, 2019. It has since been updated.